# NTP-Client

**Repository Path**: jimmygodchen/NTP-Client

## Basic Information

- **Project Name**: NTP-Client

- **Description**: No description available

- **Primary Language**: C++

- **License**: WTFPL

- **Default Branch**: master

- **Homepage**: None

- **GVP Project**: No

## Statistics

- **Stars**: 0

- **Forks**: 0

- **Created**: 2025-08-19

- **Last Updated**: 2025-08-19

## Categories & Tags

**Categories**: Uncategorized

**Tags**: None

## README

# NTP Client (Windows DLL/LIB + Console + CVI GUI)

1. [Time Synchronization via NTP](#1-Time-Synchronization-via-NTP)

2. [NTP Client Library (C++ DLL)](#2-NTP-Client---Library-C++-DLL)

2.1 [Description](#Description)

2.2 [C++ interface](#C++-interface)

2.3 [C interface](#C-interface)

2.4 [Example of Use](#Example-of-Use)

3. [NTP client - Graphical Interface (CVI)](#3-NTP-client---Graphical-Interface-CVI)

## 1. Time Synchronization via NTP

NTP has been used to synchronize time in variable response networks since

1985 and that makes it one of the oldest Internet protocols. Uses UDP

OSI layer 4 protocol and port 123. By default, it achieves an accuracy of 10 ms to 200

µs, depending on the quality of the connection.

NTP uses a hierarchical system called "*stratum*". Server of type *stratum* 0

obtains the most accurate time, for example, from a cesium clock, but is not intended for

time distribution to the network. This is done by the server of type *stratum* 1, which it receives

time from *loss* 0. Then there are servers *stratum* 2 to 15, which always

they get the time from the parent server and their number basically shows

distance from the reference clock.

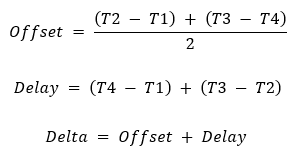

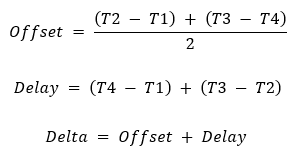

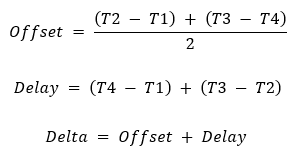

The NTP algorithm begins by sending a defined packet (RFC 5905), respectively

datagram, from client to server. The most important information transmitted by this packet

are client mode (NTPv4), *stratum* local clock, accuracy of local clock,

and especially the time **T1**, which indicates the time of the local clock at the time the packet leaves to

networks. After the NTP server receives the packet, the server writes the time **T2** to it, which

indicates the current time on the server clock and just before sending the time **T3**, which

indicates the time the packet leaves back to the network. After receiving the packet by the client, it is finally

writes the last time **T4**, which indicates the arrival back to the client. if they are

these times are measured accurately, it is enough to calculate the two resulting ones thanks to the formulas below

values. **Offset**, which symbolizes the shift of the client clock from the clock on the server and

**Delay**, which represents the delay of the packet passing through the network, which can be due

switches and network technologies are highly variable. The sum of these values then

represents the final shift of the local clock, which should ideally be

equal to zero.

## 2. NTP Client - Library (C++ DLL)

### 2.1 Description

I developed a simple and single-purpose library in C ++ in the environment

Microsoft Visual Studio 2019. I only relied on the official RFC specification

5905. The library is currently designed for Windows NT because it uses Win32

API for reading and writing system time and *Winsock* for UDP communication. However

in the future it is not a problem to extend it with directives \ #ifdef eg with POSIX

*sockets*.

Because the library contains only one **Client** class, the class diagram is

unnecessary.

```cpp

class Client: public IClient

```

The library has only two public methods, **query** and

**query_and_sync**.

```cpp

virtual Status query (const char* hostname, ResultEx** result_out);

virtual Status query_and_sync (const char* hostname, ResultEx** result_out);

```

Query is the core of the whole library. At the beginning of this method, a UDP is created first

packet, it is filled with the current values ??I mentioned in the first chapter and

sends it to the NTP server. Upon arrival, he completes the time T4 and performs the calculation, according to

formulas from the first chapter. Times are represented by the time_point class from the library

std :: chrono with resolution to nanoseconds (time **t1**) or class

high_resolution_clock (time **t1_b**).

```cpp

typedef std::chrono::time_point time_point_t;

time_point_t t1 = std::chrono::time_point_cast(std::chrono::system_clock::now());

auto t1_b = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

```

This combination is because the times in the first formula (offset) must be

absolute. These are the times **T2** and **T3** that came from the server. therefore not

use high_resolution_clock, in the second formula (delay) it is then possible to read **T1**

from **T4** use relative times, which can be obtained using high_resolution_clock.

The following formulas show the calculation using this approach, all units

variables are nanoseconds.

```cpp

double offset = [(T2 - T1) + (T3 - T4)] / 2

double delay = (T4b - T1b) - (T3 - T2)

```

By summing the values *offset* and *delay* we get *delta*, ie the value by which

adjust the local system clock. However, this only applies if the latter is used

public methods **query_and_sync**, the first mentioned will only communicate with

server and calculation.

Resulting calculated and obtained values, including *jitter* (stability indicators

network connection) is returned to the user either in the Result structure that is used for

classic C interface, or in the class ResultEx, which, unlike the first contains

time represented by class time_point_t, as opposed to time represented by classical

TimePt structure with *integers*.

```cpp

struct Result

{

struct TimePt time;

struct Metrics mtr;

};

```

```cpp

class ResultEx

{

public:

time_point_t time;

Metrics mtr;

};

```

This achieves the compatibility between C and C ++, which is required for a dynamic library.

If the user uses the library directly from C ++, it is more convenient to work with time

represented by the time_point_t class, otherwise there is no choice but to use it

structure.

```cpp

struct TimePt

{

int tm_nsec;

int tm_usec;

int tm_msec;

int tm_sec;

int tm_min;

int tm_hour

int tm_mday;

int tm_mon;

int tm_year;

};

```

```cpp

struct Metrics

{

double delay_ns;

double offset_ns;

double jitter_ns;

double delta_ns;

};

```

Error states are returned as *enumerator* Status, where 0 means success

(similar to POSIX) and anything else is a bug.

```cpp

enum Status : int16_t

{

OK = 0,

UNKNOWN_ERR = 1,

INIT_WINSOCK_ERR = 2,

CREATE_SOCKET_ERR = 3,

SEND_MSG_ERR = 4,

RECEIVE_MSG_ERR = 5,

RECEIVE_MSG_TIMEOUT = 6,

SET_WIN_TIME_ERR = 7,

ADMIN_RIGHTS_NEEDED = 8

};

```

In addition, the library contains several static stateless methods to facilitate the work

programmer, used primarily to format results and convert types.

### 2.2 C++ interface

The standard library interface for use with object-oriented languages is in

form *interface*, which exposes the two main public methods described above

**query** a **query_and_sync**. The interface is only a macro for the struct type,

of course you could use a proprietary MS **__interface**, but most of the time it gets better

stick to proven and compatible things.

```cpp

Interface IClient

{

virtual Status query(const char* hostname, ResultEx** result_out) = 0;

virtual Status query_and_sync(const char* hostname, ResultEx**result_out) = 0;

virtual ~IClient() {};

};

```

### 2.3 C interface

The interface usable for DLL calls must be compatible with classic ANSI C,

instead of classes, it is necessary to use the classic C OOP style, namely functions, structures and

*opaque pointers*. These functions must then be exported using the EXPORT macro,

which is a macro for **__declspec (dllexport)**. It is also necessary to set adequate

calling convention, in our case it is **__cdecl**, where the one calling as well

cleans the tray.

The **Client__create** function creates a library instance, which is represented

pointer, or macro, HNTP, which in the context of Windows is called

*handle*.

```cpp

typedef void* HNTP;

```

Other functions, such as **Client__query** or **Client__query_and_sync**

they take this indicator as the first argument. The rest is very similar to C++

interface, however one difference it has. Instead of delete, it must be called at the end

**Client__free_result** and **Client__close**.

```cpp

extern "C"

{

/* object lifecycle */

EXPORT HNTP __cdecl Client__create(void);

EXPORT void __cdecl Client__close(HNTP self);

/* main NTP server query functions */

EXPORT enum Status __cdecl Client__query(HNTP self, const char* hostname, struct Result** result_out);

EXPORT enum Status __cdecl Client__query_and_sync(HNTP self, const char* hostname, struct Result** result_out);

/* helper functions */

EXPORT void __cdecl Client__format_info_str(struct Result* result, char* str_out);

EXPORT void __cdecl Client__get_status_str(enum Status status, char* str_out);

EXPORT void __cdecl Client__free_result(struct Result* result);

}

```

### 2.4 Example of Use

You must have *runtime* **vc_redist** (2015-19) installed to run. Code

it is at least partially annotated and perhaps even clear. I tried to make it

use trivial. A client instance is created, the *query* function is called, and it terminates

the client. This can be done in an infinite loop with a defined interval,

to ensure constant time synchronization. The following lines are excluded

from a console application that serves as an example of use.

```cpp

enum Status s;

struct Result* result = nullptr;

HNTP client = Client__create()

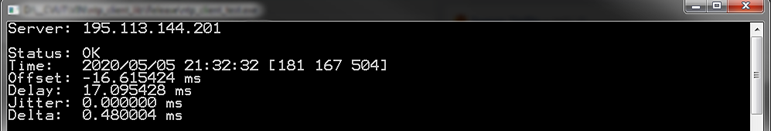

s = Client__query_and_sync(client, "195.113.144.201", &result);

Client__free_result(result);

Client__close(client);

```

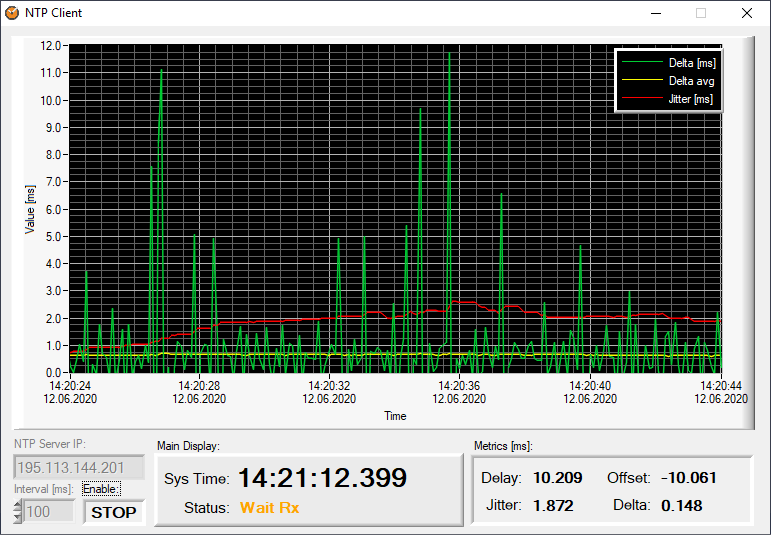

## 3. NTP client - Graphical Interface (CVI)

I used the dynamic library in the LabWindows / CVI environment to create

graphical interface of the NTP client, which is periodically called from its own thread. On

graph we then see the green delta value (the current difference of the local clock from

server), its diameter in yellow and *jitter* in network communication in red. To run

**CVI Runtime 2019** is required.